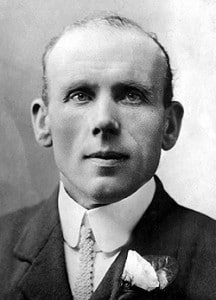

When Marwood died, in 1883, 32-year old Berry decided the police force was not for him, so he left, and finding himself desperate for a vocation in life, he opted for a macabre career; a hangman. With all the knowledge of the gallows obtained from Marwood, Berry confidently applied for his deceased friend’s job, but was turned down. The ex-policeman persisted with his unusual aspiration, and to his delight, he received his first commission of 21 guineas – to hang two men at Calton Prison in Edinburgh. Included in the commission was a second-class return rail ticket from Berry’s hometown of Bradford, and money for board and lodgings.

On the night before James Berry was due to hang the men, he had a lucid nightmare about his new life-taking occupation. In the dream, Berry found that he could not hang a man because the trapdoor on the gallows refused to open. This same disturbing dream returned to haunt Berry’s sleep many times over the years.

The following morning, everything went smoothly, and the two condemned

Lee had the reputation of being a petty thief and had been hired by Miss Keyse out of pity. With such a track record, the footman soon became the prime suspect in the eyes of the police, despite the fact that Lee had tried to put out the fire on the night of the murder, and had broken down in tears upon hearing that his mistress had been murdered. “I have lost my best friend.” A tearful Lee had said to the village constable who had arrived at the scene of the crime first.

But the police painted a different picture and went on the body of circumstantial evidence that was building up against the teenager. Lee had bloodstained clothing, and an empty can that had contained lamp oil was found in the pantry where Lee had been seen shortly before the fire broke out. Lee tried to explain everything. He told police that the blood on his clothing was his own, because he had gashed his hand while breaking a window pane to let the smoke from the fire out, although he couldn’t explain the empty can of lamp oil. Lee was arrested and charged with murder, and at the subsequent trial, the prosecution made it clear that only John Lee had a motive. Just before her brutal death, Miss Keyse had cut Lee’s weekly wages of four shillings in half because he had come under suspicion of theft. So, Lee had obviously killed her in fit of anger.

Lee protested, but his words fell on deaf ears. The jury reached a guilty verdict, and shortly before the sentence was passed, Lee declared from the dock, “I am innocent. The Lord will never permit me to be executed!” The judge sentenced John Lee to death by hanging.

After the trial, a rumor circulated that Lee’s half-sister, Elizabeth Harris, the cook, had been discovered making love with a man in bed by Miss Keyse, a rather prim, puritanical individual. According to the rumor, Miss Keyse was outraged and took a swipe at the naked couple, and out of sheer panic, Miss Harris struck back at her frail mistress with her fist, killing her. Hearsay had it that Miss Harris and her lover then took Miss Keyse’s body to the dining room, where they tried to cover up the murder by battering the dead woman’s skull in to create the impression that a violent murder perpetrated by an intruder had taken place. Miss Harris soon came to her senses and realized the police wouldn’t be so easily fooled, so she sprinkled the contents of a can of lamp-oil over the corpse and set fire to it, hoping that the flames would make the cause of Miss Keyse’s death hard to determine. But the ad hoc cremation attempt didn’t succeed, because John Lee was soon alerted by the smell of burning, and ran into the dining room with a pail of water to douse the flames. As the youth did this, Elizabeth or her lover placed the incriminating can of lamp-oil in the pantry where Lee had been working. On the night before the execution, Lee chatted in his cell with the prison governor and the chaplain, and the former told the condemned that there was no chance of a reprieve. Lee responded by shrugging. Then said, “Elizabeth Harris could say the word which could clear me, if she would.”

When the governor and the chaplain left the cell, Lee settled down and had no difficulty sleeping. The dream he had was a strange one. Lee dreamed her was standing on the gallows with the noose around his neck, but the trapdoor wouldn’t open, despite the repeated yanks the hangman was giving to the lever. When Lee awoke from the dream, he felt that God had assured him that there was nothing to worry about, as he would not die on the gallows.

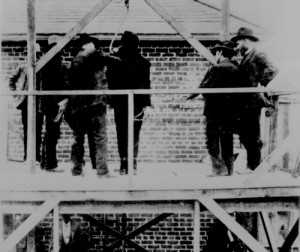

Berry trembled. He took the hood and noose off Lee and tested the stubborn trap with a sandbag that weighed the exact same weight as Lee. The trap opened this time and the sandbag crashed to the ground under the gallows. Lee was pushed onto the trap again with the hood over his head and the noose re-positioned around his neck. This time, all the witnesses to the impending execution knew that the trap would work.

Berry pulled the lever – but the trap beneath Lee’s feet wouldn’t open again. Berry’s face started to twitch, and his shaking hands took the noose and hood off Lee, and guided him off the trap. A prison engineer and Berry discussed the problem, and a carpenter was summoned. When the edges of the trap had been planed, and the bolts of the hanging apparatus had been greased, a sandbag acted as a substitute for Lee again. Everything went like clockwork. Lee was put on the trap for the third time. The hooded man stood there, waiting for Berry to throw the lever. Berry inhaled the cold morning air, then pulled the lever as hard as possible. The chaplain looked away as the greased bolts slid as expected. But to his total astonishment, the chaplain saw that Lee was still standing on the unopened trap. The holy man fainted, but was caught by a warder before he could hit the floor.

It was decided that a messenger should be sent to London to inform the Home Secretary of the botched hanging attempts. While everyone waited for the messenger to return, Lee was asked if he felt like eating a last breakfast, and he later consumed a substantial repast. Ironically, the hangman James Berry had to turn down the meal he was offered, because of his nerves. So Lee eat Berry’s meal instead.

About nine hours later, the messenger returned from London to inform Lee that he had been granted a respite by the Home Secretary. The death sentence had been commuted to life-imprisonment. But Lee was released after serving twenty years. He came out in 1905 and married a childhood sweetheart who had waited patiently for him. The couple went to America, and up until his death in 1933, John Lee, the man who couldn’t be hanged, swore he was not a murderer. Whenever people asked him what he thought about being spared from the rope three times in a row, Lee would say it wasn’t luck, or freak mechanical failure that saved his neck – but divine intervention.

By Sasha Dubronitz