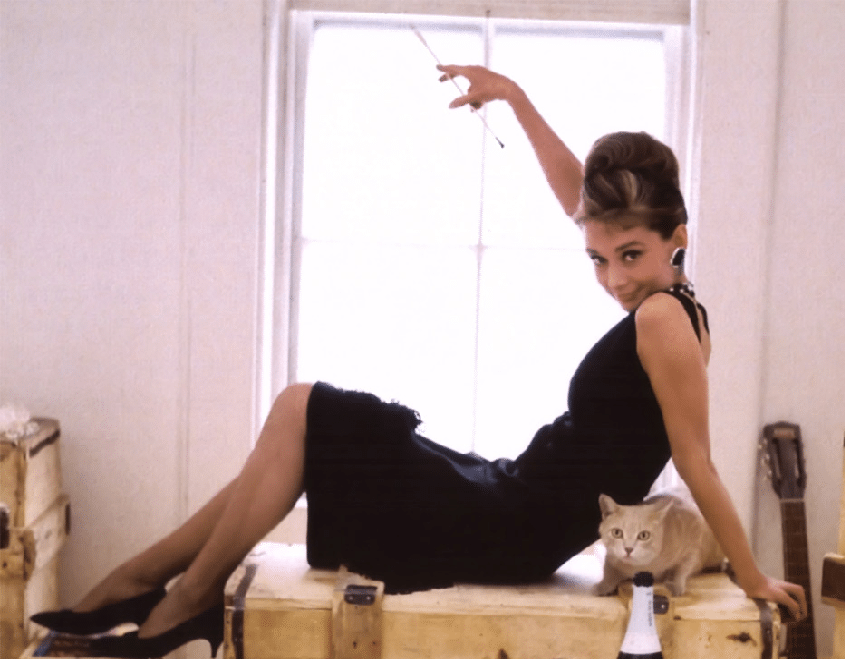

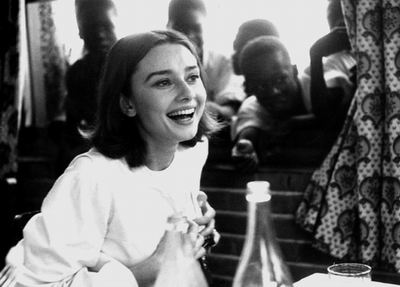

Audrey Hepburn, iconic star of Breakfast At Tiffany’s, was renowned for her waif-like figure. But her sylph-like beauty masked a lifetime of poor health which culminated in her death at only 63.

Now, a leading scientist suggests that her genes were fundamentally altered through suffering starvation as a teenager in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands.

Dr Nessa Carey adds that this link between poor diet and genetic disruption might explain why we are now increasingly suffering from modern health crises such as obesity and diabetes.

Audrey Hepburn’s enviable figure was the result of wartime deprivation. Her genes were fundamentally altered through suffering starvation as a teenager. Rates of both conditions are surging, with health scientists warning last week that half of Australian men will be obese by 2030.

Hepburn, the Belgian-born daughter of a Dutch baroness and an English banker, was staying in the Netherlands as a child when Hitler’s armies overran the country in 1940. She struggled to survive after her older brother was dragged off to a labour camp and her uncle and cousin were executed.

From November 1944 until May 1945, a period known in Dutch history as ‘the hunger winter’, she suffered terrible starvation. The Germans blockaded her area of the Netherlands, causing mass malnutrition that killed around 18,000 people.

Hepburn, 16, was reduced to eating tulip bulbs and trying to make bread from grass. She spent the war’s closing days hiding from the Nazis in a cellar.

Hepburn’s slight figure (her waist was only 20in) came not from any celeb-style fad diet. It was a legacy of the jaundice, anaemia, respiratory problems and chronic blood disorders she contracted in those desperate days.

After a lifetime of quietly suffering frail health, she died in 1993, two months after undergoing an operation for colon cancer. She said of her privations, ‘After living for years under the Germans, you swore you would never complain about anything again.’

Hepburn’s slight figure was a legacy of jaundice, anaemia, respiratory problems and chronic blood disorders.

Now Dr Carey, a biology expert and former senior lecturer, has written a book in which she suggests Hepburn’s poor health was the result of genetic changes caused by her terrible childhood diet.

Such changes are being revealed by the new science of epigenetics.

We are beginning to understand how we are not simply born with genes that are pre-set for life. Vast numbers of them can be changed ‘epigenetically’ by our environments and diets. Genes can be switched on or off by this process, or the way in which they function can be altered.

Hepburn’s case is one among thousands of hunger winter victims that have been studied since the war. Their records reveal vital clues about the serious damage that bad diets can wreak. Thanks to excellent record-keeping in the Netherlands, scientists have been able to follow people there for more than five decades.

Indeed, the latest analysis of the figures, announced last week, revealed that malnutrition in childhood is linked to coronary heart disease in later life. This effect could be due to the poor nutrition of these early years permanently affecting metabolism.

The most worrying finding is that parents’ poor nutrition can seriously affect the health of their unborn children. This is particularly true of mothers who are malnourished in the first three months of pregnancy.

While the hunger winter survivors’ babies tended to be born at a normal size, they often inherited a lifetime problem: their obesity rates are much higher than normal.

Some theories suggest that when a baby suffers malnutrition in the womb, a survival mechanism kicks in that pre-sets its metabolism in preparation for being born into a world of famine and starvation. This epigenetic alteration causes the body to give priority to fat storage over a developing robust liver, heart and brain.

Scientists have yet to pinpoint all of the genes that can be affected by bad diet

Recent studies of these offspring show that hunger winter babies may suffer other problems in old age, too, including a greater incidence of dementia.

Some of these effects even seem to be present in the children of this group…the grandchildren of the original hunger winter survivors. Not only were the children’s genes changed epigenetically, but those harmful changes have been passed on through two generations.

Fathers’ diets may also play a crucial role, according to studies of people living in an isolated region of northern Sweden called Overkalix.

In the early 20th century, the region suffered terrible food shortages thanks to failed harvests, interspersed with periods of great plenty, when many people would stock up and eat as much as they could.

Researchers have found that, in fathers who ate a surfeit of food in the years leading up to puberty, their sons and grandsons are at increased risk of dying from diabetic illnesses, compared to children who grew up in the same region whose fathers did not overeat during this crucial period of puberty.

Because Overkalix was so isolated, its inhabitants were genetically strongly related. So it can be shown that the unusually obese children’s metabolic problems were caused by an epigenetic change.

Scientists have yet to pinpoint all of the genes that can be affected by bad diets. But earlier this year, Cambridge University scientists found one gene that can be altered in children of mothers who had an unhealthy diet during pregnancy.

It is called Hnf4a and when altered it leaves the children with an increased risk of type-2 diabetes, heart disease and cancer later in life.

The research found the gene plays a crucial role in ensuring the pancreas produces sufficient levels of insulin…the hormone that controls our blood-sugar levels.

The study on human tissues shows that poor nutrition in the womb weakens the effect of Hnf4a when children grow into adulthood, increasing the risk of diabetes.

Dr Susan Ozanne, who led the study, says, ‘We are starting to understand how nutrition in the womb shapes our long-term health by influencing how the cells in our body age.’

But the research is not all doom and gloom. Scientists are also discovering how, by making small changes in our diet, we may protect ourselves and our offspring from dangerous epigenetic alternations.

For example, new laboratory studies show that expectant mothers who eat a diet rich in B vitamins…found in green leafy vegetables…may reduce the risk of their children suffering from cancers of the stomach, colon and rectum, all of which are major causes of death in the western world.

Scientists believe the B vitamins bolster the work of tumour-suppressing genes in the gut.

For most of us, it would be difficult to work out what dietary sins our mothers committed while pregnant. But we can all adopt the sort of diet that may protect us against some of the epigenetic problems we might have inherited.

There are two strong additional reasons for doing so: such a diet is in itself a very healthy regime; and might help to protect our unborn children against future problems, too.

According to findings in the journal Clinical Epigenetics, chemical components in some foods can actually switch on genes that suppress tumours while silencing those that promote their growth.

These foods include grapes, tomatoes, tofu, parsley, garlic, turmeric — and those two almost-ubiquitous health foods, broccoli and green tea.

As Dr Nessa Carey, author of the new book The Epigenetics Revolution, concludes the new studies show that following a healthy diet is more than just a matter of personal responsibility. It is our duty to future generations.

‘Maybe the old saying “we are what we eat” does not go far enough.

Maybe we are also what our parents ate and what their parents ate before them,’ she says.

by Susan Floyd