James Bond tried one. So, too, did writers Jack (On The Road) Kerouac and J.D. (Catcher In The Rye) Salinger.

The artist who created Shrek swore by his, and spent half an hour inside it at least once a day.

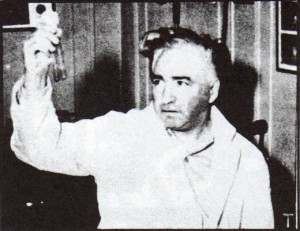

They were all devotees of the original love machine, invented in the Fifties by psycho-analyst and therapist Dr Wilhelm Reich as a pathway to a better, if not the best ever, sexual experience.

In some ways, you can’t help feeling sorry for Austrian-born Reich…a disciple of Sigmund Freud in Vienna…who escaped from Adolf Hitler to the U.S. just before World War II.

There he was, a prophet for the health- giving power of the guilt-free sexual climax. He coined the phrase ‘sexual revolution’ and devoted his life as a psycho-analyst to freeing us all from our repressive Victorian selves.

Then, on the verge of the Swinging Sixties, with society about to hitch up its skirts and go sex mad, he died, and missed out on the supposed pleasure of his own Utopia.

Yet, according to author Christopher Turner in a new biography of Reich, Sean Connery had one at the height of his James Bond fame.

But whether sitting in the box delivered what its designer promised is another matter. If Connery was shaken or stirred, he never said. William Steig, author of the original Shrek comic book, revealed his gave him ‘an inner vibration, a little bit like an orgasmic feeling’ — which is a long way from blowing your socks off.

American author Norman Mailer, who desperately searched for what he called the ‘apocalyptic’ sexual experience, admitted just before he died that he never achieved it with his version.

Perhaps they were all just bonkers, you may think. But there was method…of a sort…in Reich’s madness. More importantly, his

There is a direct link from his sanctification of free love and instant sex to the excesses of today’s permissive society.

At the beginning, however, Reich was a star turn in developing the discipline of psycho-analysis in the early years of the 20th century. As a shrink, he believed people needed to be freed from their inhibitions. But then he went out on a limb of his own with a radical theory.

The release that came with sexual climax, he declared, was the key to a healthy mind and healthy body — and, indeed, as the scope of his vision expanded, to a healthy world.

It would not only cure neurotics of their fears, but war-mongering fascists of their odious beliefs. ‘Make love not war’ was his belief long before it became a Sixties slogan.

But his ambition didn’t stop there. Reich was convinced he had discovered the very essence of life, a universal and eternal force that he named ‘orgone’ — hence the official name of his wooden box: the ‘Orgone Energy Accumulator’.

Orgone was not unlike the concept of the ‘libido’ his old teacher Freud had identified — except Reich insisted his life force had a physical presence, which manifested itself in glowing microscopic particles of matter he called ‘bions’.

It was the physical harvesting and harnessing of ‘orgone’ from the atmosphere that was the purpose of his sex machine — which was best used, he said, in direct sunlight, in open country and well away from electricity power lines.

The wood in its construction absorbed the free-flying ‘orgone’ from the skies, while layers of metal kept it insulated inside.

By concentrating the life force in this ‘accumulator’, he claimed, its users were charged up, much like a car battery plugged into the mains, and then experienced the sexual ecstasy that would free their minds and bodies.

That the box heated up, he claimed, was proof of its ability to attract natural energy. Sceptics, however, suggested that confining someone inside an insulated container on a hot day was bound to lead to raised temperatures, but not necessarily anything else.

Reich was undaunted. The potential of his contraption was, he maintained, limitless. It could heal the sick and even eliminate cancer tumours. It was the panacea the world had been waiting for. ‘I am the discoverer of life energy,’ he maintained confidently.

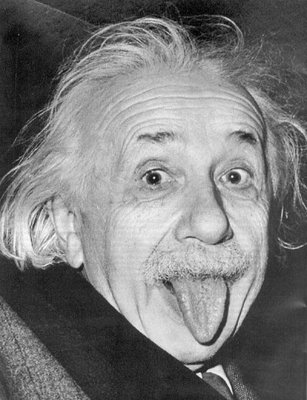

The great man examined the evidence and dismissed Reich’s theory as scientific nonsense. ‘Orgone’, he declared, simply did not exist. Thereafter he refused to take Reich’s calls or discuss the matter.

Slighted, rejected as a quack by the international psycho-analysis community and as a charlatan by the scientific one, Reich became increasingly paranoid. Everyone became a suspected enemy, even his ex-wife and daughter. Having become a virtual recluse at his home in Maine, he got on with building his accumulators — 250 in all — for a small number of thrill-seekers.

Most were members of the emerging Beat generation of writers and artists, attracted by his unconventionality and his endorsement of free love.

But then he fell foul of the law. The cures he claimed for his accumulator were judged by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be false and misleading, and a court injunction ordered him to stop selling and distributing them.

When he ignored the ban, he was jailed for two years in 1956 and his remaining machines destroyed. Piles of his books were burned by the authorities, an echo of what the Nazis had done to his work.

His supporters suspected a conspiracy to silence him because of the subversive nature of his ideas.

He died in prison, from a heart attack, in November 1957. His legacy, the love machine, ended up in a Museum of Questionable Medical Devices, alongside a foot-operated breast enlarger and a vacuum-powered hair restorer.

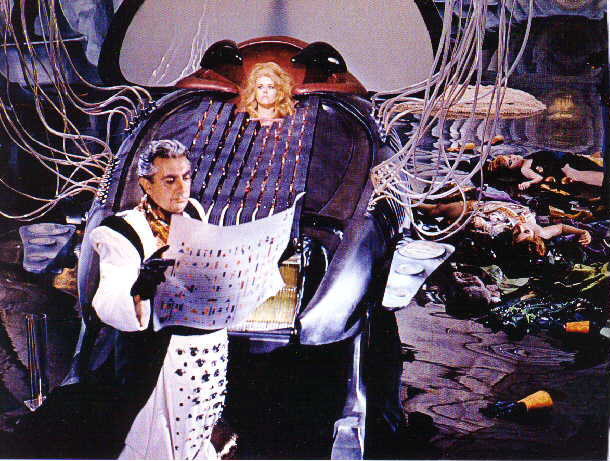

But it took on a new life in popular culture. It inspired Jane Fonda’s ecstasy as she was tucked up inside a so-called ‘Excessive Machine’ in the 1964 cult sci-fi parody Barbarella, and put the smile on Woody Allen’s face after he stepped out of an ‘Orgasmatron’ in Sleeper (1973). It was Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘big, bright green pleasure machine’.

But Reich’s cultural impact went far deeper than jokey slots in films and songs. In many ways, it was his endorsement of sexual release that put the swinging into the Sixties. Sex was good, restraint was bad. Our permissive, sex-saturated century has its origins in Reich’s so-called science.

It was not meant to work out like this, of course. According to his theories, once the shackles were off, the world would be a better place. It hasn’t proved true. In an article analysing Reich, Time magazine concluded that America was one giant ‘orgone’ box. ‘From innumerable screens and stages, posters and pages, it flashes larger-than-life-sized images of sex. The message is sex will save you.’

Astonishingly, that description was of 1964, an era that now looks positively quaint. In the 47 years since then, all semblance of restraint seems to have been abandoned.

Two conflicting interpretations flowed from Reich’s love contraption. ‘To the bohemians,’ says his biographer, Christopher Turner, ‘it was a liberation machine, the wardrobe that would lead to Utopia. But to conservatives it was Pandora’s box, out of which escaped anarchism and promiscuous sex.’

There, if you’ll forgive the expression, is the rub. And how has it turned out?

Germaine Greer was asked about the influence of his theories on The Female Eunuch, her ground-breaking 1970 book about women’s liberation.

‘We did think freeing sexuality would allow virtue to flower,’ she said. ‘We were wrong, I think.’ Her words could serve as Reich’s requiem, carved on one of his orgasmatrons and, along with the legacy of the Sixties he inspired, laid to rest.

by David Livingstone