It is now becoming popular for women to eat the placenta as part of their childbirth experience.

They expect to experience major health benefits like prevented or reduced postpartum depression. A couple of celebrities mentioned it and that brought placentophagia into the spotlight. What’s going on?

“Placentophagia” pertains to ingestion of placenta, fluids, and tissues by mothers during delivery. The behavior, which is almost universal among nonhuman mammals (whales and dolphins are exceptions), is virtually absent in human cultures, past and present. There are occasionally individuals or groups who do it, but they are an exception and not the rule. Eventually someone will do anything conceivable to the human mind; for instance, search the web for “man eats airplane.”

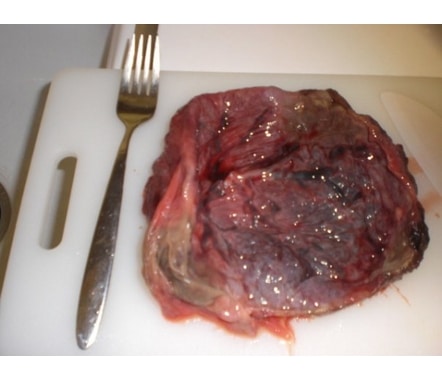

Today we are in the midst of another placentophagia fad. Women, reporting encouragement by midwives and aided by unverified web information, are deciding to ingest placenta at delivery. They eat it raw, cooked, blended into smoothies, or dried and encapsulated, in order to prevent or reduce negative aspects of childbirth, such as postpartum depression, “baby blues,” fatigue, lactational insufficiency and hormone deficiencies.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence showing that placentophagia by humans medically or physiologically ameliorates any of these problems. However, websites of doulas, midwives and commercial placenta encapsulators often assert that placentophagia at delivery is useful because, for instance, dried human placenta has been used for centuries in Chinese herbal medicine. Actually, Zi He Che, as it is known, is used on rare occasions to treat a variety of ailments from impotence and infertility to tinnitus and chronic cough. First, its specific effects, if any, cannot be isolated because it is always blended with many other herbs or medicines. Second, there are no scientific studies showing that it is effective at all. The same can be said for treatments like hornet nest or turtle shell for cancer, Chinese dates for ADD/ADHD and pearl, antelope horn, or earthworm for epilepsy.

There are documented benefits of placentophagia in animals, relating primarily to enhancing pain relief during labour and delivery, and helping to produce immediate maternal behavior at delivery because of the mother’s attraction to afterbirth material on the young. Nonhuman mothers find afterbirth irresistibly attractive at delivery, but clearly human mothers do not. Furthermore, for animals, the methods of preparing and administering afterbirth material are essential. For women engaging in placentophagia these parameters are irrelevant. The urban legends, anecdotes and testimonials all indicate positive results regardless of method of preparation, time of ingestion relative to birth, and amount ingested. What only seems to matter is that they expected it to work before they did it. This is a classic formula for a placebo effect — an improvement based on expectation, not on pharmacological mechanisms.

Even though human afterbirth contains the same analgesia-enhancing component as that of other species, we do not yet know whether this component, or others, has an effect on human problems.

Actually, placebo effects can occur even when beneficial components are present. About 100 years ago, Brown-Sequard developed a treatment for impotence consisting of injections of extracts of ground testes from other species; French surgeon Serge Voronoff developed a method of grafting pieces of testes from other species onto the testicles of his impotent patients. Both were successful; many patients experienced a return of potency. The fact that testes secrete testosterone was not yet known. However, Brown-Sequard’s extract did not contain testosterone; and Voronoff’s grafts were rejected and could not have secreted testosterone. Why then did so many of their patients experience positive effects on potency? Because they expected to.

Are placebos necessarily bad? Many experts say no, as long as the placebo is not harmful, and as long as taking it does not delay or replace needed scientifically validated medical help. So, can placentophagia be harmful to humans? The near absence of placentophagia among humans, when compared to the near universality of the behavior in other mammals, has to be considered seriously. The contrast suggests that it may have been occasionally harmful to humans, or otherwise evolutionarily maladaptive. Afterbirth can be contaminated by microorganisms, can contain toxins filtered from blood, or even have negative immunological consequences for the mother.

Even a tiny adaptive disadvantage can have evolutionary significance over thousands of generations.

by David Livingstone