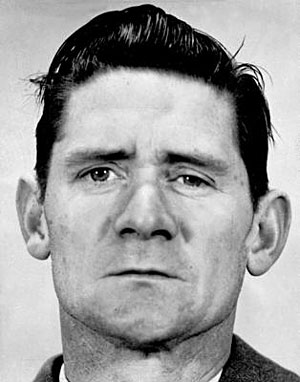

Ryan was a stylish—if spivvy’—dresser, who usually wore expensive, well-cut suits, silk tie and a fedora. He was always keen to impress as a man of means and consequence. He was of above-average intelligence and was described by the people who knew him and prison authorities as a likable character but also a compulsive gambler. It was said that his arresting officer thought him to be a partcularly tough person to question and gave nothing, at least until the game was up.

Ronald Ryan was born in Carlton, Melbourne in 1925. His poverty stricken childhood was marked by the alcoholism and abuse by his parents. In November 1936, the plight of the Ryan children was bought to the attention of the state welfare authorities. Ronald was sent to Rupertswood, a Salesian Order’s school for orphaned, wayward and neglected boys. Ryan’s three sisters were made wards of the state a year later after authorities declared them as “neglected”. The three sisters were sent to the Good Shepard Convent in Collingwood. Ryan absconded from Rupertswood in September 1939 and with his half-brother George Thompson, worked in and around Balranald, NSW, spare money earned from sleeper cutting and kangaroo shooting was sent to his mother looking after their sick alcoholic father.

At the age of twenty, Ryan had saved enough money to rent a house in Balranald, NSW. Ron then collected his sisters and mother and they all lived in this house. Ryan’s father stayed in Melbourne and died a year later aged 62 after a long battle with miners’ disease phthisis tuberculosis.

When Ryan turned 22, he decided to join his brother who was tomato farming near Tatura in Victoria. Ryan started to visit Melbourne at the weekends. It was on one of these weekend trips that Ryan met his future wife Dorothy George. On 4 February 1950, Ryan married Dorothy Janet George at St Stephen’s Anglican Church in Richmond. He converted from a Catholic to Church of England to marry her. He converted back to Catholicism shortly before his execution. Dorothy was the daughter of the Mayor of the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn. Ryan and Dorothy had three daughters, Janice, Wendy and Rhonda. A fourth baby was stillborn.

After spending a few months working for his father-in-law as a trainee mechanic, Ryan decided that more money could be made cutting timber near Marysville. When it was too wet to cut timber, Ryan got a job painting for the State Electricity Commission.

Trouble with the law started when his rented house burnt down. Ryan was away for the weekend in Melbourne when the arsonist struck. The arsonist was caught and claimed that Ryan had put him up for it, he also claimed that Ryan wanted the house burnt to claim insurance money. In his first appearance in court, in 1953, he was acquitted on a charge of arson.

In 1956 Ryan appeared in court for passing bad cheques in Dandenong. He was given a bond. His next appearance in court was after he issued a large number of forged cheques in Warrnambool. His partner was caught with the goods purchased with the bad cheques and handed Ryan over to the police. He received another a good-behaviour bond. The arresting detective gave a favourable character reference on Ryan’s behalf.

After being apprehended for robbery in April 1960, Ryan and his accomplices escaped from the Melbourne City Watch House but were recaptured several days later. On 17 June 1960, Ryan pleaded guilty in the Melbourne Court of General Sessions to eight charges of breaking and stealing and one of escaping from legal custody. He was sentenced to eight and a half years imprisonment.

Ryan first served prison time at Bendigo Prison. Here, he appeared to want to rehabilitate himself. His time in prison was productive and he exhibited a disciplined approach to study, completing his Leaving Certificate (the equivalent of 11 years of formal schooling). He was studying for his Matriculation (the successful completion of 12 years of formal schooling) when he was released on parole in August 1963. He was regarded by the authorities as a model prisoner.

After working as a clerk for a couple of months, Ryan went to lunch and never returned. He had started robbing butcher shops and used explosives to blow their safes.

Ryan and two accomplices were caught after another butcher shop robbery

This is where he met fellow prisoner Peter John Walker (who was serving a 12 year sentence for bank robbery). When Ryan was informed that his wife was getting a divorce, he made a plan to escape from prison. Walker decided to go along with him. Ryan planned to take himself and his family and flee to Brazil, where there was no extradition treaty with Australia.

On Sunday 19 December 1965, Ryan and Walker put the escape plan into effect. As prison officers were taking turns attending a staff Christmas party in the officers’ mess hall, Ryan and Walker scaled a five-metre prison wall with the aid of two wooden benches, a hook and blankets. Running along the top of the wall to a prison watch tower, they overpowered prison warder Helmut Lange and took his M1 carbine rifle. Ryan threatened Lange to pull the lever which would open the prison tower gate to freedom. Lange, however, deliberately pulled the wrong lever. Ryan, Walker and Lange then proceeded down the steps to the tower gate, but it would not open. At the bottom of the stairs was the night officers’ lodge. Warder Fred Brown was returning from lunch to relieve Lange when he was confronted by the escapees. Brown did not resist. When Ryan realised Lange had tricked him, Ryan jabbed the rifle into Lange’s back and marched him back up the stairs so Lange could pulled the correct lever to open the tower gate. The two escapees then exited the gate out into the prison car park.

To Ryan and Johns dismay there were only two cars in the car park and one had a flat tyre.

However, the duo did find prison chaplain Brigadier James Hewitt in the car park. They grabbed him and used him as a shield. Ryan, armed with the rifle, pointed it at Hewitt and demanded his car. Prison Officer Bennett in Tower 2 saw the prisoners. Ryan called to Bennett to throw down his rifle. Bennett ducked out of sight and then got his rifle.

When Hewitt told Ryan he didn’t have his car that day, Ryan rifle butted him in the head causing serious injuries. Les Watt, a petrol attendant who watched the escape from the petrol station on Sydney Road, witnessed Ryan hitting Hewitt with the rifle. They both then left the badly injured chaplain and Ryan ran to nearby Champ Street.

Walker moved to the next door church. Prison officer Bennett had his rifle aimed at Walker and ordered Walker to halt or he would shoot. Walker took cover behind a small wall that bordered the church.

The prison alarm was raised by Warder Lange, and it began to blow loudly, indicating a prison escape. Unarmed warders, Wallis, Mitchinson and Paterson, came running out of the prison main gate, onto the street.

George Hodson, who had been having lunch in the prison officers mess near the number 1 post, responded to Lange’s whistle. Bennett shouted to Hodson he had a prisoner, Walker, pinned down behind the low church boundary wall. Hodson headed for Walker and picked up Walker’s pipe. Hodson grappled with Walker but the escapee managed to break free so Hodson began hitting the fleeing Walker over his head with the piece of pipe. Walker was a faster runner than Hodson, so Hodson continued to chase after Walker with the pipe still in his hand. Both men ran towards the armed Ronald Ryan.

Meanwhile, confusion and noise were gaining strength around the busy intersection of Sydney Road and O’Hea Street, with the armed Ryan waving the rifle around trying to get cars to stop so he could commandeer them, and people ducking for cover between cars.

Frank and Pauline Jeziorski were travelling south on Champ Street and had slowed to give way to traffic on Sydney Road when Ryan armed with the rifle appeared in front of their car. Ryan threatened the driver and his passenger wife to get out of their car. The driver, Frank Jeziorski, turned his car off, put it in neutral then got out of his vehicle. Ryan got in via the driver’s door. Amazingly, Pauline Jeziorski refused to get out of the car. She was persuaded by Ryan to get out of the car, only to go back in the car to get her handbag. Paterson, realising Ryan was armed, returned inside the prison to get a rifle.

Warder William Mitchinson was first to reach the car and grabbed Ryan through the driver’s window, he told Ryan “the game’s up”. Warder Thomas Wallis who was following, ran to Mrs Jeziorski’s side of the car. He grabbed Mrs Jeziorski and pulled her away from the car.

In frustration, Ryan forced Mitchinson to back off, then got of out the passenger’s side door and noticed Walker running towards him, being chased by Hodson who was holding the pipe in his hand. Walker was shouting frantically to Ryan that prison guard William Bennett, standing on the number 2 prison tower, had his rifle aimed at them. At this time, Hodson was chasing Walker, Ryan took a couple of steps forward and raised his rifle and aimed it at Hodson.

George Hodson fell to the ground. He had been struck by a single bullet, travelling from front to back. The bullet had exited through Hodson’s back, about an inch lower than the point of entry in his right chest. Hodson died in the middle of Sydney Road.

Paterson, now with a rifle, ran back outside and onto Champ Street. He decided he could not get a clear shot, so he stood on a low wall in the prison’s front garden. He aimed his rifle at Ryan, and claimed he fired a shot in the air when a woman came into his line of sight.

Ryan and Walker ran past the fallen warder and commandeered a blue vanguard driven by Brian Mullins, with Walker driving the car drove through the service station and driving away on O’Hea Street.

On 24 December 1965, the Victorian Government announced a 5,000 pounds (AU$10,000) reward for information leading to the capture of Ryan and Walker.

On Christmas Eve there was a party at the flat. John Fisher, who knew Ryan and Arthur Henderson, boyfriend of the tenant, were there. After all the beer was consumed, Walker and Henderson left to find a more drinks. An hour later Walker returned alone to the flat. He had killed Henderson in a Middle Park toilet block. Henderson was shot in the back of his head by Walker. The escapees left the flat and returned to Kensington. On the 26th two women were charged with harbouring the criminals, they came forward after Henderson was killed and the escapees had left. The charges were later dropped.

The pair return to hiding in the basement of the house in Kensington, Murray was given money to buy a car in Sydney and return with it. Ryan and Walker left for Sydney on New Year’s Day, arriving on 2 January 1966.

After arriving in Sydney, Walker made contact with an ex-girlfriend he knew and arranged a double date to meet the woman and a friend at Concord Repatriation Hospital. The date was arranged for the evening of 6 January. Unknown to the escapees the woman tipped off the police. Detective Inspector Ray Kelly and a heavily-armed contingent of 50 police officers and detectives set a trap for them.

When the escapee’s car pulled up near the hospital, Ryan walked over to a nearby telephone box, but it had been deliberately put out of order, so he walked over to a neighbouring shop and asked to use the phone there. The owner had been instructed to tell Ryan that his phone was also out of order, and as Ryan walked out of the shop he was tackled by six detectives, dropping a loaded .32 revolver that he had been carrying. At the same moment Det. Sgt Fred Krahe thrust a shotgun through the car window and held it at Walker’s head. He was captured without a struggle.

Ryan and Walker were on the run for 19 days.

In the boot of the car Police found 3 pistols, a shotgun and two rifles (all fully loaded), an axe, jemmy, two coils of rope, a hacksaw and two boilersuits.

According to police, Ryan admitted to them he had shot prison officer Hodson. However, these verbal allegations were not signed by Ryan and he denied making such verbal or written confessions to anyone. The only signed document by Ryan was that he would give no verbal testimony. Walker was also tried for the shooting murder of Arthur James Henderson during the period when he and Ryan were at large.

On 15 March 1966, the case of “The Queen vs Ryan and Walker” began in the Supreme Court of Victoria. The first day was spent choosing the make up of the jury. Ryan and Walker both exercised their legal right in objecting to twenty candidates each.

The bullet that killed Hodson had past through his body and was never recovered. The Crown’s case relied on eyewitnesses when Hodson was killed. Each witness testified a different account of what they saw and where Ryan was standing. Eleven eyewitnesses testified they saw Ryan waving and aiming his rifle. There were variations, whether Ryan was standing, walking or squatting at the time a single shot was heard, and whether Ryan was to the left or right of Hodson. Only four eyewitnesses testified that they saw Ryan fire a shot. Two eyewitnesses testified they saw smoke coming from Ryan’s rifle. Two eyewitnesses testified they saw Ryan recoil his rifle. Some witnesses testified they saw Ryan’s rifle recoil when he fired and that they saw smoke from Ryan’s rifle. The owners of the car Ryan got in, Frank and Pauline Jeziorski, were two of the witnesses. Warder Thomas Wallis testified that he saw smoke come out of the rifle Ryan was holding. Pauline Jeziorski testified that she smelt gunpowder after Ryan had fired the shot.

At trial, all prison officers testified that they did not see Hodson carrying anything, and they did not see Hodson hit Walker. However, two witnesses, Louis Bailey and Keith Dobson, testified that they saw Hodson carrying something like an iron-bar/baton as he was chasing after Walker. Governor Grindlay testified that he didn’t see a bar near Hodson’s body but he found one after Hodson’s body was loaded into an ambulance.

Detective Sergeant KP Walters told the court that on 6 January 1966, the day after his re-capture in Sydney, Ryan said “In the heat of the moment you sometimes do an act without thinking. I think this is what happened with Hodson. He had no need to interfere. He was stupid. He was told to keep away. He caused his own death. I didn’t want to shoot him.”

If the shot was in a downward angle the bullet would have hit the road forty feet from where Hodson was hit, it also suggested that Hodson could have been shot from another elevated point and possibly by another prison officer. It would cast doubt that Ryan had fired the fatal shot. But the prosecution argued that Hodson (6 feel 1 inch (1.85 m) tall could have been running in a stooped position, thus accounting for the bullet’s fatal angle of entry.

Despite extensive search by police, neither the fatal bullet nor the spent cartridge were ever found. Although all prison-authorized rifles were the same M1 carbine type, scientific forensic testing of the bullet would have proven which rifle fired the fatal shot — every rifle leaves a microscopic “unique marker” on the fired bullet as it travels through the barrel of the rifle.

All the bullets in Ryan’s rifle would be accounted for if Ryan cocked the rifle with the safety-catch on, this faulty operation (conceded by prison officer Lange, assistant prison governor Robert Duffy, and confirmed by ballistic experts at trial) would have caused an undischarged bullet to be ejected, spilling onto the floor of the guard tower. Opas established that a person who was inexperienced in handling that type of rifle and its cocking-lever rifle, it would be easy to jam the rifle and any attempt to clear the jam would result in a live round being ejected.

On the eighth day of the trial Ryan was sworn in and took the witness stand. Ryan denied firing a shot, denied the alleged verbal (unsigned) confessions said to have been made by him, and denied ever saying to anyone that he had shot a man. According to Ryan, they were after the reward money by making false allegations.“At no time did I fire a shot. My freedom was the only objective. The rifle was taken in the first instance so that it could not be used against me”.

After a trial in the Victorian Supreme Court lasting twelve sitting days Ryan was convicted of the murder of Hodson and sentenced to death by Justice John Starke, the mandatory sentence at that time. Asked if he had anything to say before sentencing Ryan stated “I still maintain my innocence. I will consult with my counsel with a view to appeal. That is all I have to say!”

Walker was found not guilty of murder, but guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment. He would later be found guilty of manslaughter for the death of Arthur Henderson and receive another 12 years sentence.

When it was apparent that the Victorian Government was intent on hanging Ryan, juryman Tom Gildea contacted the nine other jury members he could trace. Gildea said that of the twelve jurors, three refused to sign petitions, one older man who was convinced of Ryan’s guilt and the two who believe Ryan was not guilty. Two other jurors could not be contacted. Seven jury members, including Gildea, signed separate petitions requesting Ryan’s death sentence be commuted to life in prison. Later, some of the jurors came forth and stated they would never have convicted Ryan of murder had they known that he would in fact be executed.

Ryan had a right to increased free legal assistance for expert forensics analysis, to hire expert witnesses, and to present a series of appeals and recourses that were available to those facing execution by the government. The Full Court agreed that it was unthinkable that a man should be executed before he had exhausted his ultimate right of appeals.

On December 12, 1966 The State Executive Council ( Premier Bolte’s cabinet) announced that Ryan would hang on January 9, 1967.

Opas, convinced of Ryan’s innocence, agreed to work without pay. Opas consulted the Ethics Committee of the Bar Council to seek approval to make a public appeal for a solicitor prepared to brief him, as Opas was prepared to pay his travel, other expenses and appear without fee. The Committee said that this would be touting for business and was unethical. Opas argued that a man’s life was at stake and he could not see how he would be touting when no payment was involved. Opas defied the ruling and on national radio sought an instructor. Opas was inundated with offers and accepted the first application, being from Ralph Freadman. Alleyne Kiddle was in London completing a Master’s degree and she agreed to take a junior brief without a fee.

Opas then flew to London to present Ryan’s case to the highest judges in the Commonwealth. Ryan’s execution was reluctantly delayed by Premier Bolte awaiting the Privy Council’s decision. However, Bolte took no chance of the possible that Her Majesty might give a decision contrary to the advice of the Judicial Committee.

On January 23, 1967 The Privy Council Judicial Committee refuse Ryan leave for appeal.

On January 25, 1967 The State Executive Council set Ryan’s execution date as January 31.

Bolte schedules Ryan’s execution on the morning of Friday February 3, 1967 and had insisted that the death sentence be carried out.Bolte’s cabinet was unanimous although there were at least four State cabinet members who opposed capital punishment.

Melbourne newspapers The Age, The Herald and The Sun, ran campaigns opposing the hanging of Ryan, the papers traditionally supporters of the Bolte government, deserted him on the issue and ran a campaign of spirited opposition on the grounds that the death penalty was barbaric.

Churches, universities, unions and a large number of the public and legal

Bolte denied all requests for mercy and was determined Ryan would hang.

On the afternoon of the eve of Ryan’s hanging, Dr Opas appeared before the trial judge Justice John Starke. Opas was seeking a postponement of the execution, due to the opportunity of testing new proferred evidence. Opas pleaded with Starke, and said; “Why the indecent haste to hang this man until we have tested all possible exculpatory evidence?” But Starke rejected the application.

That evening, a former Pentridge prisoner Allan John Cane, arrived in Melbourne from Brisbane in a new bid to save Ryan. An affidavit by Cane, which was presented to Cabinet, says he and seven prisoners were outside the cookhouse, when they saw and heard a prison warder fire a shot from the No. 1 guard post at Pentridge Prison, on the day Hodson was shot. Police had interviewed these prisoners but none were called on at the trial to give evidence. Cane was immediately rushed into conference with his solicitor Bernard Gaynor, who tried to contact Cabinet Ministers informing them of Can’s arrival. Gaynor telephoned Government House seeking an audience with The Governor Sir Rohan Delacombe. However, Gaynor was told by a Government House spokesman that nobody would be answering calls until 9 am in the morning (one hour after Ryan’s scheduled execution.) Gaynor said Cane’s mission had failed.

At 11 pm, Ryan was informed that his final petition for mercy had been rejected. More than 3,000 people gathered outside Pentridge Prison in protest to the hanging. Shortly before midnight more than 200 police were at the prison to control the demonstrators.

The night prior to the execution, Ryan was transferred to a cell, just a few steps away from the gallows trapdoor. Father Brosnan was with Ryan most of this time. In the eleventh-hour Ryan wrote his last letters to his family members, his defence attorney, the Anti-Hanging Committee and to Father Brosnan. The letters were handwritten on toilet paper inside his cell and neatly folded. In the documentary film The Last Man Hanged Ryan’s letter to The Anti-Hanging Committee is read out loud to the public. Ryan wrote; ” … I state most emphatically that I am not guilty of murder.” Ryan’s last letter was to his daughters, it contained this line With regard to my guilt I say only that I am innocent of intent and have a clear conscience in the matter

Ryan was hanged in ‘D’ Division at Pentridge Prison at 8:00 am on Friday 3 February 1967.

Ryan refused to have any sedatives but he did have a nip of whisky, and walked calmly onto the gallows trapdoor. Ronald Ryan’s last words were to the hangman; “God bless you, please make it quick.”

A nationwide three-minute silence was observed at the exact time that Ryan was hanged. Thousands of people protesting outside the prison knew the moment of the execution because the pigeons on the D Division roof all took flight.

Later that day, Ryan’s body was buried in an unmarked grave within the “D” Division prison facility.

Nineteen years after Ryan’s execution, former Warder Doug Pascoe, confessed on-air to Channel 9 and the media, that he fired a shot during Ryan’s escape bid. Pascoe believes his shot may have accidentally killed his fellow prison guard, Hodson. Pascoe had not told anyone that he fired a shot during the escape because at that time, “I was a 23-year-old coward”. In 1986, he tried to sell his story but his claim was dismissed by police, because his rifle had a full magazine after the shooting and he was too far away.

Retired prison Governor Ian Grindlay said Ryan allegedly told him straight out that he had shot but not meant to kill Warder Hodson.

Sister Margaret Kington of the Good Shepherd Convent in Abbotsford, said Ryan told her that he had shot Mr Hodson, but had not meant to kill him.

The man who saw Ronald Ryan commit the murder for which he became the last man hanged in Australia has broken a 25 year silence. Les Watt wrote to the Australian newspaper stating let me assure you and your readers that Ryan did kill Hodson.. Watt broke his silence after reading Philip Opas comments and his forthcoming autobiography where he thought that Opas had certainly distorted the facts which led to the suggestion that maybe Ryan did not pull the trigger that kill Hodson.

Although verbal confessions are not permissible in court, in the 1960s the public and therefore the jury, were much more trusting of the police.

In 1993, a former Pentridge prisoner Harold Sheehan claimed he had witnessed the shooting but had not come forward at the time. Sheehan saw Ryan on his knees when the shot rang out and therefore, Ryan could not have inflicted the wound that passed in a downward trajectory angle that killed Hodson.

All prison authorized M1 rifles were issued with eight rounds of bullets, including the rifle seized by Ryan from Lange. Seven of the eight rounds were accounted for. If the eighth fell on the floor of the prison watch tower when Ryan cocked the rifle with the safety catch on, thereby ejecting a live round, then the bullet that killed Hodson must have been fired by a person other than Ryan.

Ryan gave evidence and swore that he did not fire at Hodson. He denied firing a shot at all. Ryan denied the alleged verbal confessions said to have been made by him. Dr Opas says the last words Ryan said to him were, “We’ve all got to go sometime, but I don’t want to go this way for something I didn’t do.“

On 23 August 2008, Dr Philip Opas QC, died after a long illness at the age of 91. Opas maintained Ryan’s innocence to the end.

Mr. Justice Starke the judge at Ryan’s trial, and a committed abolitionist, was convinced of Ryan’s guilt but did not agree Ryan should hang. Until his death in 1992, Starke remained troubled about Ryan’s hanging and would often ask his colleagues if they thought he did the right thing. Philips Opas junior in the trial Brian Bourke was filmed in 2005 and said One of the problems of Ryan’s trial was an alleged admission that he made on the plane back to the homicide fellows, those sort of things can’t happen now because they’ve got to be recorded on tape but whether he made the admission or was verballed, I don’t know. He was a pretty talkative fellow, he might have. I didn’t have much doubt about his guilt.