It was perhaps an unusual form of affirmation. But for Lucy Hawking, her father’s reaction as she read out part of a children’s novel over dinner at his Cambridge home was vital and thrilling.

‘I was reading a draft to him and he laughed so much he jumped out of his chair,’ she recalls. ‘Two of his carers had to catch him and put him back.

‘That’s when I knew he was hooked on the whole thing, that he’d started to enjoy this.’

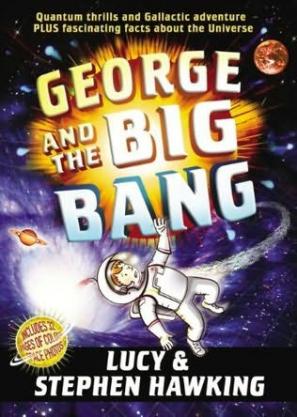

‘This’ being a rather surprising father-and-daughter collaboration. For in recent years Stephen Hawking, the brilliant theoretical physicist, has co-authored a series of science-based children’s books with his daughter Lucy.

The peculiar mix of fame, physics and disability has often left his family…including first wife Jane and sons Robert and Tim…feeling, Lucy says, ‘trapped in another chapter of the Stephen Hawking story’.

Stories later emerged suggesting Mason was abusive to Hawking. It was alleged he had regularly required treatment for unexplained cuts and bruises.

Lucy was one of several people who reported her fears to the authorities…but Hawking refused to co-operate, and the police dropped the investigation.

Meanwhile, Lucy had her own troubles: the breakdown of her marriage to UN worker Alex Mackenzie Smith and the discovery that their young son William had autism.

In 2004, she checked into a rehabilitation clinic in Arizona to be treated for depression and alcohol problems.

‘It was a catastrophic time. I think as a family we had our own “falling into a black hole” moment,’ she says, finding a metaphor in the astronomical object central to her father’s work.

‘Part of coming out of that was to do something that had meaning. Working with Dad to write the books and inspire kids seemed a way of making a contribution.’

The idea for the books arose at William’s seventh birthday party. ‘William’s friends were all gathered around Dad asking questions – “Stephen, what would happen to me if I fell into a black hole? What would it feel like?”

‘I realised this was how they could understand information, by making it relevant to them.’

It’s tempting to assume Hawking had little to do with characters or plot, but Lucy insists he now plays a key part in the creative process.

‘In the first book he saw his part as consultant scientist, ensuring it was accurate and educational,’ she says.

‘By the second he’d got into the swing of it. For the third he came up with the plot about a mysterious group who want to destroy the Large Hadron Collider and stop the secrets of the early universe becoming known.

‘So he went from being quite teacherly to, “What the hell, I’m writing the story.” ’

The writing process has been a bonding experience, with father and daughter meeting frequently over dinner at his Cambridge home.

‘It’s been lovely for both of us.

‘I know Dad never expected to work with any of his children professionally, least of all me because I was so firmly in the arts, so he’s taken a great deal of pleasure from that.’

For her part, the experience has reinforced Lucy’s pride in her 69-year-old father’s determination.

‘He has transcended his condition so successfully that people sometimes forget what he has to struggle against physically.’

Hawking relies on a muscle in his cheek to communicate, using it to fire an infrared beam attached to the arm of his glasses which in turn moves the cursor on a screen dictionary he uses to select words.

‘There is a sense of recreating a past there,’ says Lucy. ‘But I don’t think it’s overwhelmingly sad. He doesn’t see it that way.

‘He loves the idea of an alter ego who actually gets to visit outer space rather than just thinking about it all the time.’

Having spent much of her childhood as a carer to her disabled father, the discovery of her son’s autism was, Lucy says, a heavy blow.

‘When William was very small I was aware something wasn’t right, but I just kept thinking it can’t be, because lightning doesn’t strike twice. Then when he was diagnosed with autism I thought, “How? How is this possible?” I felt quite angry.’

The stress contributed in part to the breakdown of her marriage.

Now 13, William is thriving, Lucy says. He accompanied his mother to America when she took up a year’s residency as a writer at Arizona State University.

‘I knew upping sticks was unusual, particularly given William’s condition, but I was facing turning 40 in the town where I grew up and I wanted to ring the changes,’ she says.

‘Arizona has an exceptional autism research association so I knew we had back-up. And William loved it there. He played basketball and learned to ride like a cowboy. He really gained in confidence.’

Returning from America in June, she and William set up home in London, although they still see Stephen regularly. Grandfather and grandson share a sweet, uncomplicated bond.

‘In America we had a day out to Universal Studios with Dad,’ says Lucy. ‘William was holding on to Dad’s wheelchair like a little bodyguard. He has no concept at all of my father as famous – what he understands is he’s in a wheelchair. He was just looking after him.’

It is an image that must, a few years ago, have seemed impossible. ‘Dad has this thing he talks about in one of his lectures, that black holes aren’t as black as they’ve been painted,’ says Lucy.

‘His discovery was that you can get out of a black hole. At the end of the lecture he says what it all adds up to is, if you find yourself in a dark place, don’t despair, because there is a way out. I always think of that as a nice way of putting what has happened.’

by Debbie Dot